Hello everyone, after hearing all week people complaining about the latest Oscar De La Hoya fight I decided to post this research document I did for my college dissertation, it was a six months research document that in reality just took 9 weeks to put together but it was good enough to get my degree!

It’s a long read but I would love to see what you guys think of it, I only covered De La Hoya’s first 10 years of his career, but i touch on social issues that are ongoing even today. Grab some coffee and enjoy the read!

Between Two Worlds:

The Biography

In the year 1992 an unknown young amateur pugilist was the only American to win a boxing gold medal at the 1992 Summer Olympic Games in Barcelona, Spain. That day the name of Oscar De La Hoya was born as a public figure. After his Olympic triumph De La Hoya decided to start his career as a professional boxer, collecting an impressive record of 31 fights with 26 Kos (knock outs) and 4 boxing titles (WBC Welterweight Championship, WBC Super Lightweight Championship, IBF [International Boxing Federation] Lightweight Championship and the WBO Lightweight Championship).

After De La Hoya won the Olympic gold medal in 1992, he became a promising star for boxing and consequently he started to be a promising marketable product because of his unconventional looks as a boxer. Media, specially press media, began to market the “Golden Boy” image based more on his looks than on his boxing achievements.

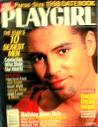

De La Hoya was seen literately as “golden” because of the sudden attraction of women and money. Random sponsors started to offer him money for television commercials, photo shots, magazine covers, and television appearances. Also, his looks started to attract female audiences who normally would not associate themselves to boxing, a sport conventionally seen as manly. De La Hoya attracted this audience through his masculine appeal, rather than his athletic abilities or the fact that he had won an Olympic gold medal (to what actually the term “golden” makes reference). This was clearly seen as an unexplored gold mine by his sponsors and management to the point that HBO promoted De La Hoya fight against Pernell Whitaker in 1997 in Los Angeles as “Painfully Handsome.”

De La Hoya was seen literately as “golden” because of the sudden attraction of women and money. Random sponsors started to offer him money for television commercials, photo shots, magazine covers, and television appearances. Also, his looks started to attract female audiences who normally would not associate themselves to boxing, a sport conventionally seen as manly. De La Hoya attracted this audience through his masculine appeal, rather than his athletic abilities or the fact that he had won an Olympic gold medal (to what actually the term “golden” makes reference). This was clearly seen as an unexplored gold mine by his sponsors and management to the point that HBO promoted De La Hoya fight against Pernell Whitaker in 1997 in Los Angeles as “Painfully Handsome.”

Despite his early achievements, he struggled to be accepted as a respectable boxer among the Mexican and Mexican-American communities at his hometown in East L. A.; one of the strongest boxing markets in the US. Many boxing fans speculated that he was too young and not tough enough to be embraced as a champion in comparison to legendary Mexican fighters like Raton Macias, Pipino Cuevas, Chiquita Gonzales, and most recently Julio Cesar Chavez. Others critiqued that he just was not Mexican enough, his image did not represent the community he claimed to belong to. De La Hoya was accused of using the barrio (neighborhood) image only when it was convenient to attract the Mexican fans and their market. Critics argued that De La Hoya’s management created a boxing profile for the mass media. He was portrayed as the kid from the barrio who represented the lower classes of East Los Angeles. But De La Hoya invested more time at the golf clubs hanging out with the Hollywood celebs than interacting with the community or learning about their needs.

Oscar De La Hoya’s biggest challenge was to convince his critics that he was ready to become the next boxing warrior who would bring pride to the Mexican community. He got this opportunity when he was offered to fight Julio Cesar Chavez, the most popularly and admired boxer of the late 20th century among the Mexican community. However, his victory over J.C. Chavez backfired and only drew more hatred than respect from Mexicans.

Oscar De La Hoya’s biggest challenge was to convince his critics that he was ready to become the next boxing warrior who would bring pride to the Mexican community. He got this opportunity when he was offered to fight Julio Cesar Chavez, the most popularly and admired boxer of the late 20th century among the Mexican community. However, his victory over J.C. Chavez backfired and only drew more hatred than respect from Mexicans.

The Questions

Why did the Mexican community in southern California not perceived Oscar De La Hoya as an honorable boxer? Why did this community reject De La Hoya? What factors played a role for Mexicans to refuse to recognize De La Hoya as Mexican? To what degree being a Mexican-American is different from being a Mexican? What are the perceptions of one group towards the other and what are the complications that these perceptions create on their social relationship?

The emphasis of this project is to analyze why the image used by De La Hoya’s management to market him corrupted the established images of boxing for the Mexican community. His calculated management not only diminished his credibility as boxer but also showed lack of loyalty and pride, which are two qualities deep-rooted in Mexican culture.

Oscar: The Early years in East LA

Oscar De La Hoya was born February 4, 1973, in Los Angeles, California. His parents, Cecilia and Joel, moved to the United States from Mexico. The neighborhood in which De La Hoya grew up was safe, but trouble lurked right around the corner (Kawakami 8-9).

La Hoya was a typical untroubled kid from East LA who went to school and spent time with his friends. Many times, however, he would come home running from bullies that threatened him. He would hide in his bedroom in fear that his dad would find out. His father Joel De La Hoya, a former pro boxer, never made much of the situation until it repeated itself a few times. De La Hoya would always run home crying. He would cry for everything. It got to the point that his father became concerned about Oscar and his fighting incompetence. He believed that Oscar was too much of a pushover. “Los Hombres no lloran” [men don’t cry] was Oscar first lesson to learn on the road to becoming a man (Kawakami 18-20).

La Hoya was a typical untroubled kid from East LA who went to school and spent time with his friends. Many times, however, he would come home running from bullies that threatened him. He would hide in his bedroom in fear that his dad would find out. His father Joel De La Hoya, a former pro boxer, never made much of the situation until it repeated itself a few times. De La Hoya would always run home crying. He would cry for everything. It got to the point that his father became concerned about Oscar and his fighting incompetence. He believed that Oscar was too much of a pushover. “Los Hombres no lloran” [men don’t cry] was Oscar first lesson to learn on the road to becoming a man (Kawakami 18-20).

The best solution was to have him go to the boxing gym. Like Oscar, his father had been forced to go into boxing by a father who also had amateur boxing experience in the 1940’s (Kawakami 10-11).

Oscar’s first experience with boxing gloves was at the age of 5, when his brother Joel Jr. put a pair of gloves on him and another pair on his cousin for a sparring session. As soon as the fighting started, Oscar covered his face in fear while his cousin landed a left jab right on his nose. As a result, Oscar started crying and ran home, similar to his previous experiences with over-bearing bullies (Kawakami 10-12).

De La Hoya never pictured himself as a fighter. It was actually his older brother Joel Jr. who many believed had the potential to become a great fighter. Oscar’s father, Joel Sr., also believed that Oscar’s older brother was a better fighter. Joel Jr. never pictured his younger brother as a fighter. “Oscar hated physical confrontations, he never had a street fight. He preferred to play with skateboards near the house and baseball in the park. Nothing violent,” (Sports Illustrated, 1993). But boxing is in the De La Hoya tradition and blood. It goes back several generations when his grandfather, Vicente, a 126-pound amateur in the 1940s, and his father Joel Sr., fought in Mexico as a lightweight in the professional ranks in the mid-1960s (Kawakami 10-12).

De La Hoya never pictured himself as a fighter. It was actually his older brother Joel Jr. who many believed had the potential to become a great fighter. Oscar’s father, Joel Sr., also believed that Oscar’s older brother was a better fighter. Joel Jr. never pictured his younger brother as a fighter. “Oscar hated physical confrontations, he never had a street fight. He preferred to play with skateboards near the house and baseball in the park. Nothing violent,” (Sports Illustrated, 1993). But boxing is in the De La Hoya tradition and blood. It goes back several generations when his grandfather, Vicente, a 126-pound amateur in the 1940s, and his father Joel Sr., fought in Mexico as a lightweight in the professional ranks in the mid-1960s (Kawakami 10-12).

De La Hoya was being pushed to go to the gym and learn to defend himself by the time he was 6 years old. He started going to the Eastside Boxing Gym in East LA. “As soon as I started going to the gym,” he explained, “I thought I have to be tough. No more crying. The incentive for my development as a boxer was my family,” (Sports Illustrated, 1993). Oscar loved the attention he received from his family, “Every time I won a fight, my cousins, aunts and uncles would give me money. A dollar here, a quarter there, half a buck.” (Sports Illustrated, 1993)

Road to the Olympic Dream

De La Hoya’s idol as a child was the legendary Sugar Ray Leonard, a gold medal winner at the 1976 Summer Olympics as a professional boxer. Oscar quickly began to reach success. In 1988, he won the national Junior Olympic 119-pound championship at age 15 and the next year he won the 125-pound title.Two years later, De La Hoya won the national Golden Gloves 125-pound title, and the same year was the youngest U.S. boxer at the Goodwill Games, where he won a gold medal. He followed that success with a victory in the 1991 U.S. Amateur Boxing 132-pound tournament. The USA Boxing named De La Hoya the 1991 Boxer of the Year (Kawakami 30-40).

Based on his success, experts made De La Hoya a favorite to win a gold medal at the 1992 Summer Olympics. He lost only once at an international competition and defeated the two-time world champion Julio Gonzalez of Cuba on the day of his prom at Garfield High School in 1991. De La Hoya claimed a place on the U.S. boxing team by winning the 132-pound class gold medal at the 1991 U.S. Olympic Festival, defeating Patrice Brooks. “How good is Oscar? One in a million,” asked Manuel Torres, director of boxing at the Resurrection gym to Sports Illustrated. (Sports Illustrated, 1991)

Just when De La Hoya’s career seemed to be unstoppable, he faced two difficult adjustments. First, he split with his longtime trainer, Al Stankie, who had helped train another East Los Angeles boxer, Paul Gonzales, to an Olympic gold medal. Stankie had a serious problem with alcohol addiction. “It was very hard, but I had to let him go,” (Sports Illustrated 1991).

De La Hoya then began training with Robert Alcazar, a friend of his father.

“Oscar is so different from the boxers that I have worked with because he knew what he wanted to do with his life at an early age. He realized that he wanted to be a boxer, and each year I work with him I see him progressing,” (Hispanic Magazine 1995).

A personal tragedy caused De La Hoya an even more difficult second adjustment. His mother Cecilia died after suffering from breast cancer. Cecilia De La Hoya was her son’s biggest fan (Kawakami 58+). “My mother would get mad at me when I didn’t want to go to the gym because I wanted to be with my friends. She would say, ‘No, you go to the gym because you are going to be a champion’” (Hispanic Magazine 1995).

After his mother’s death, De La Hoya dedicated every victory to her. “It’s just a way of saying, ‘For you’” (Kawakami 62+). Before she died, Cecilia De La Hoya asked her son to win the Olympic gold medal for her. According to De La Hoya “That was [his] motivation” (Sports Illustrated 1991).

Barcelona ’92: Living the Dream

De La Hoya won the right to represent the United States at the 1992 Summer Olympics by winning a decision over Patrice Brooks at the Olympic. De La Hoya was the favorite to win the lightweight gold medal at the 1992 Summer Olympics in Barcelona, Spain (Kawakami 63+). “The kid has all the tools,” said Pat Nappi, former U.S. national boxing team coach to Sports Illustrated. “Right now, based on what I’ve seen, he has the gold medal,”(Sport Illustrated, 1991).

De La Hoya won the right to represent the United States at the 1992 Summer Olympics by winning a decision over Patrice Brooks at the Olympic. De La Hoya was the favorite to win the lightweight gold medal at the 1992 Summer Olympics in Barcelona, Spain (Kawakami 63+). “The kid has all the tools,” said Pat Nappi, former U.S. national boxing team coach to Sports Illustrated. “Right now, based on what I’ve seen, he has the gold medal,”(Sport Illustrated, 1991).

As the Olympic tournament began he defeated of his first three opponents, knocking out the first. Then in his first medal round match, De La Hoya struggled against his opponent’s awkward bull-rushing style, but Oscar was able to contain his opponent as he emerged with a tight one-point victory (Kawakami 66+).

De La Hoya was now in the gold medal bout, and all the other U.S boxers had already failed to bring home the gold. His final hurdle would come against Marco Rudolph, the fighter who had defeated Oscar one year earlier at the World Championships in Australia. It was De La Hoya’s first loss as an amateur in four years. De La Hoya dominated the fight from beginning to end. He controlled Rudolph for the entire three rounds. In the third round, he used his powerful left hand to knock down Rudolph. It was no contest and Oscar had accomplished his ultimate goal (Kawakami 72+).

The “Golden Boy” Turns Pro

De La Hoya’s amateur record now stood at 223 wins, 5 losses, with 153 knockouts. His Olympic victory won De La Hoya the nickname “Golden Boy.” Having reached his goal of winning the gold medal, he decided to turn professional. This was a difficult choice for Oscar since his mother had not wanted him to fight for money (Kawakami 84+).

De La Hoya made his professional debut in November 1992, knocking out Lamar Williams in the first round in Los Angeles. He won his first title, the World Boxing Organization (WBO) junior lightweight championship, in March 1994. De La Hoya knocked out titleholder Jimmi Bredhal of Denmark in only his twelfth professional fight. He added his second title, the WBO lightweight title, in July 1994 by knocking out Jorge Paez in the second round (Kawakami 86+).

On February 18, 1995, De La Hoya fought John Molina, the International Boxing Federation (IBF) junior lightweight champion. De La Hoya won the fight, but struggled with Molina’s tough style. The fight made him realize that he needed a more experienced trainer than his father’s friend, Robert Alcazar. Oscar hired Jesus “The Professor” Rivero to be his new cornerman (Kawakami 90+).

In May 1995, De La Hoya knocked out Rafael Ruelas in less than five minutes. He sent Ruelas to the canvas twice in the second round before referee Richard Steele stepped in to stop the fight. “He’s quick,” Ruelas told Sport Illustrated after the fight. “That left hook? I didn’t see it” (Hoffer 1995). The victory added the IBF lightweight championship to De La Hoya’s WBO belt and raised De La Hoya’s record to 18-0. In September 1995 De La Hoya scored a technical knock out against Genaro Hernandez, handing the boxer his first defeat in 34 fights (Kawakami 114+).

Despite his success, some critics said that De La Hoya had not fought enough quality opponents. Many boxing fans, especially in the knowledgeable Hispanic community, thought De La Hoya was not tough enough to be a champion (Kawakami 114+). “I’m a fighter who doesn’t get hit, who doesn’t have cuts or bruises, and that’s the reason why the fans don’t appreciate my boxing,” De La Hoya explained to Sports Illustrated in 1996. “If I was cut up, if I was all beat up and looked like a ‘fighter’, they would appreciate me more because I would look like a warrior”(Sports Illustrated, 1996).

In June 1996, De La Hoya faced his biggest challenge ever. He was scheduled to fight Julio Cesar Chavez, the World Boxing Council (WBC) super lightweight champion. Chavez was an excellent fighter and a legend in Mexico and among Hispanic fans. He had 99 professional fights and 32 title bouts, an incredible amount of experience, and had lost only one fight in his career (Kawakami 154+).

In June 1996, De La Hoya faced his biggest challenge ever. He was scheduled to fight Julio Cesar Chavez, the World Boxing Council (WBC) super lightweight champion. Chavez was an excellent fighter and a legend in Mexico and among Hispanic fans. He had 99 professional fights and 32 title bouts, an incredible amount of experience, and had lost only one fight in his career (Kawakami 154+).

De La Hoya sparred with Chavez as an amateur, and knocking him down. Oscar defeated him on the main event soundly and cut Chavez’s eye and broke his nose, but felt honored to be in the ring with such a true warrior and boxing legend (Kawakami 154+).

However, this honor was seen as shame among the Mexican community. According to Kawakami, everyone hoped that Chavez would win but they were conscious that Chavez was in his way out, after all, this was his 100th professional fight. After the fight, Oscar said “I need many more fights to learn, many years more to become a complete champion like Chavez’s has proven to be” (Sport Illustrated, 1996).

Chavez planed to retire after this fight, months before the fight took place. Once again, De la Hoya had taken advantage of the situation to prove his aptitude as a boxer. In the Mexicans’ eyes, beating the old lion Chavez to the extend of humiliation (Oscar masked Chavez’s face with blood by opening Chavez’s injured eyebrow and braking his nose) was nothing but dishonorable (Kawakami 154+).

Chavez planed to retire after this fight, months before the fight took place. Once again, De la Hoya had taken advantage of the situation to prove his aptitude as a boxer. In the Mexicans’ eyes, beating the old lion Chavez to the extend of humiliation (Oscar masked Chavez’s face with blood by opening Chavez’s injured eyebrow and braking his nose) was nothing but dishonorable (Kawakami 154+).

“De la Hoya has proved to be a warrior, for all his recent dalliance with the vanity press (what boxer, of any era, has been featured in such publications as Harper’s Bazaar and Vibe?), had earned the right to cup his own hands in future news conferences” (Sport Illustrated, 1996).

“The fight was an impressive landmark in what will surely be one of the sport’s most spectacular careers. ‘Oscar had the chances to be one of the greatest of all time,’ said promoter Bob Arum, who has nursed the former Olympian along to his first $9 million payday- a shrewd exploitation of cultural tension among the Mexican and Chicanos- and has positioned De La Hoya for more paydays just like it. He is in short, the Sugar Ray Leonard of his era, charismatic outside the ring and hit-man cool inside” (Sport Illustrated, 1996).

Oscar considered that a victory over Chavez would consolidate him as the best Mexican fighter at his hometown or at least would gain the respect he had been denied in the past by this community. Instead, he gained even more repulsion (Kawakami 155+).

What are the factors that created such a dislike for Oscar among Mexicans in Southern California given the fact that his career proves him to be the most remarkable sportsman from Mexican descendancy of the 1990’s, comparable to Fernando Valenzuela in the 1980’s?

What are the factors that created such a dislike for Oscar among Mexicans in Southern California given the fact that his career proves him to be the most remarkable sportsman from Mexican descendancy of the 1990’s, comparable to Fernando Valenzuela in the 1980’s?

One of the main conflicts is articulated by Sports Illustrated in the June 1996 edition when it mentions that “De La Hoya will never win over the entire crowd, no matter how desperate his quest for support becomes. On Friday [the day of the fight against Chavez] his team colors were half Stars and Stripes and half Mexican flag. But it is not citizenship that is at stake. By now De La Hoya’s values are so stubbornly suburban that he can never again be identified with the rough-and-tumble barrio culture that inspired him to fight. He wants to play golf? He wants to study architecture? He wants to retire by age 28?” (Sports Illustrated 1996).

The Theories

My research led me to the conclusion that the conflict between De La Hoya and his community was based on two factors. First, the different conceptualization of the word “Macho” by Mexicans and Mexican-Americans. Second, a deep-rooted social conflict between Mexicans and Mexican-Americans, in which Mexico historically, economically, and politically has been inferior to the United States.

The basic information was essentially collected from three books: Hombres y Machos by Alfredo Mirandé, Profile of man and culture in Mexico by Samuel Ramos, and The Meaning of macho: being a man in Mexico City by Mathew C. Gutmann. Their studies and materials formulate much of my theories retrospectively.

The Art of Being a Macho

Machismo in contemporary times and literature is associated to Mexicans and Latino men as part of their socio-economical construct. Machismo is defined as a ritualistic display of masculinity. Males display their masculinity through a series of characteristics that are socially defined as masculine; however, under a Mexican framework such characteristics differ depending on the sophistication of the social group that defines masculinity (Mirande 6+).

The origins of machismo in the Mexican community is debatable, but what has been agreed, by the few ethnographers who studied this subject in depth, is that the understanding of the role of being a macho differs based on social class. Males of Mexican descendancy who belong to a middle-upper class tend to have a positive view of the concept of being a macho while those who belong to middle-lower class understand the role from a negative point of view (Mirandé 77+).

Mexican males of middle-upper class define the role of being a macho in a positive perception with behaviors that are usually associated to a gentleman, which reflect education, morality, and class. According to Mirandé:

“Un hombre que es macho [a man that is a macho] is not hyper masculine or aggressive, and he does not disrespect or denigrate woman. Machos, according to the positive view, adhere to a code of ethics that stresses humility, honor, respect of oneself and others, and courage. Rather than focusing on violence and male dominance, this view associates macho qualities with the evolution of a distinct code of ethics, …being a ‘macho’ is not manifested by such outward qualities as physical strength and virility but by such inner qualities as personal integrity, commitment, loyalty, and, most importantly, strength of character” (Mirandé 67).

Mexican males from a lower social status perceive the role of being a macho from a negative perspective with behavioral traits that relay on physical potential rather than sophistication. Mirandé explains that for lower class Mexicans a macho is “the counterpart to La Chingada [The Fucked Woman] or el Gran Chingón [The Fucker], who is powerful and aggressive and goes about committing chingaderas [atrocities] and ripping up the world,”(Mirandé 36).

The History Behind el Gran Chingón

While Mirandé describes a macho as el Gran Chingón, the counterpart to La Chingada, Ramos takes this concept further to argue that these individuals take this role in an attempt to mask deep-seated feelings of inferiority, insecurity, powerlessness, and failure culturally dragged from the Conquista [Conquest] (Ramos 56).

In Mexican folklore La Chingada is not the Mexican’s real mother but his mythical, violated, metaphorical “mother”, who is symbolized by the thousands of native women raped by the conquistadores (Mirandé 36). Mirandé expands this theory by explaining that:

“According to this view, the so-called cult of machismo developed as Mexican men found themselves, unable to protect their women from the Conquista’s ensuing plunder, pillage, and rape. Native men developed an overly masculine and aggressive response in order to compensate for deeply felt feelings of powerlessness and weakness. Extending the sexual analogy further, whereas La Chingada is passive and inert, El Chingón is wounding and penetrating. Thus the Mexican male is said always to be distrustful of others para que no se lo chinguen (so that he is not ‘fucked over’)” (Mirand 36).

In Mexican culture this ideology of portraying masculinity through the use of machismo is best exemplified by the social character known as the pelado, “a term that defies translation but literately means ‘plucked’, ‘naked’, or ‘stripped’ and connotes a ‘lowly person’ or ‘nobody’” (Ramos 57+).

Like the Gran Chingón ideology, the pelado exposes his masculinity through physical attributions, not only of sexual potency but also any type of social empowerment that the reproductive organ provides (Ramos 60+). “Thus the success of any man is always attributed to his ‘balls’. The pelado may lack economic power and social status but he consoles himself by strutting around holding his genitals and exclaiming, ‘!Tengo muchos huevos!’ [I have a lot of balls]” (Ramos 60+).

Pride for the Underdog

Nevertheless, the sense of insecurity or inferiority is not something that is exclusive of those who lack social status, rather, it is something that haunts Mexican men in general (Ramos 68).

Ramos proposes that the Pelado [lower class] uses machismo to mask his insecurity or inferiority, but the middle and upper classes mask his feelings of inferiority through imitation, especially imitation of sophisticated cultures such as European and American (Ramos 18).

Because of geographical reasons the US has more notorious effects of transculturalization among Mexicans than European cultures do. However, the consumption of the cultural values that are borrowed from the U.S. requires expenses that are out of reach for those who lack economic fluency. Therefore the cultural assimilation becomes exclusive for those Mexicans who can afford to imitate activities like a Cancun spring break vacation or driving Ford 150 pickups and Mustangs in unpaved rural roads in Mexico.

The Mexican who migrates to the US transport these social issues between the middle/upper class and the lower class into Southern California, on the absence of Mexican upper class the immigrant manifest his sense of insecurity or inferiority through friction with the Mexican-American/Chicano community. The immigrant community, considering that most Mexican immigrants come from rural areas and lower social class, place Chicanos in the U.S. in a higher level of hierarchy because of their advantage on language and social empowerment. Chicanos are seen as American and are placed in a higher social level by default.

The Mexican immigrant will take an underdog position when he faces the Chicano, a relationship in which the Mexican will always feel cautious and distrustful of the Chicano’s intention to acquire his culture. The Mexican will take an instinctive underdog mode to build security; this position is a safe zone because as the underdog he has nothing to lose when he feels threaten.

Mexicans seem to identify vicariously with the person who ‘bears with it’, who is brave, que no se deja [who doesn’t take crap from anyone], and que no se raja [who doesn’t back down], especially if the person is depicted as an underdog and of poor or humble origins (Mirandé 42).

Take for instance the the case of Mexican revolutionary Francisco “Pancho” Villa’s invasion of the United States, which was celebrated by Mexicans because it demonstrated his audacity in taking on the most powerful nation in the world. In the end, what mattered was not that the battle was won or lost or that numerous casualties were incurred but rather what was important was that Villa tenía huevos (he had balls) and he was man enough to take on the hated yanquis (Mirandé 42).

The Mexican Yanqui

Oscar experienced this social friction among Mexicans and Chicanos in Southern California for the first time when he fought another southern California rising star, Rafael Ruelas, in 1995. Oscar was clearly the favorite to win this match, he was by far a better fighter than Ruelas, so choosing him as a stepping stone only instigated the social clash with the Mexican community. Ruelas was celebrated for his audacity to take on the Gringo knowing he was overmatched, at the end all that mattered was that Ruelas had the balls to exchange blows with the Gringo Goliath.

Oscar experienced this social friction among Mexicans and Chicanos in Southern California for the first time when he fought another southern California rising star, Rafael Ruelas, in 1995. Oscar was clearly the favorite to win this match, he was by far a better fighter than Ruelas, so choosing him as a stepping stone only instigated the social clash with the Mexican community. Ruelas was celebrated for his audacity to take on the Gringo knowing he was overmatched, at the end all that mattered was that Ruelas had the balls to exchange blows with the Gringo Goliath.

The article “Glory and Sorrow” written by Richard Hoffer for Sports Illustrated narrates how this fight had a backfire effect on De La Hoya. Oscar and his management saw the fight as the next step to gain recognition among the Mexican community in southern California but ended up being the opposite. Ruelas was considered a local hero, a humble but respected fighter coming up from the bottom. Ruelas was seen as the Mexican Cinderella story, a hard working immigrant who was on the rise to become a great fighter. De La Hoya thought that by defeating Ruelas, the fans would finally pay him the respect he had been long denied as the real rising star. Hoffel narrates in his article that:

It is likely that Rafael, whose hard-scrabble character added enough flavor to the bout to help generate a purse of almost $3 million, will become little more than a footnote to De La Hoya’s career. He served his promotional purpose, playing the popular foil to attract the local fans: the underprivileged kid vs. the arrogant Olympic gold medal winner. Ruelas was a winning accomplice to that extent. He was the Mexican street urchin who, after slipping across the border with a phony birth certificate, stumbled into boxing when his brother Gabriel tried to sell candy in the Goossen gym in the San Fernando Valley. Rafael was also the hardworking guy of minimal ring refinement. Though he was the underdog, Ruelas probably did as much as or more to sell the fight in the Hispanic community in LA (the fight garnered much less attention in elsewhere) than the similarly bilingual De La Hoya. Indeed, Ruelas was cheered lustily upon his appearance in the ring on Saturday. De La Hoya, who would seem to draw from the same constituency, was loudly booed (Hoffer 1995).

It is likely that Rafael, whose hard-scrabble character added enough flavor to the bout to help generate a purse of almost $3 million, will become little more than a footnote to De La Hoya’s career. He served his promotional purpose, playing the popular foil to attract the local fans: the underprivileged kid vs. the arrogant Olympic gold medal winner. Ruelas was a winning accomplice to that extent. He was the Mexican street urchin who, after slipping across the border with a phony birth certificate, stumbled into boxing when his brother Gabriel tried to sell candy in the Goossen gym in the San Fernando Valley. Rafael was also the hardworking guy of minimal ring refinement. Though he was the underdog, Ruelas probably did as much as or more to sell the fight in the Hispanic community in LA (the fight garnered much less attention in elsewhere) than the similarly bilingual De La Hoya. Indeed, Ruelas was cheered lustily upon his appearance in the ring on Saturday. De La Hoya, who would seem to draw from the same constituency, was loudly booed (Hoffer 1995).

The welcoming ovation on the ring puzzled Oscar, given the fact that they both were fighting at their hometowns and Oscar had accomplished far more than Rafael had done in his career. This was even a bigger incentive to win the match, to win his community’s respect (Kawakami 98). De La Hoya wanted to prove to this community that he was ready for greatness, it was important to win the Mexican community in southern California in order to transcend into the bigger market south of the border where the big money was.

The welcoming ovation on the ring puzzled Oscar, given the fact that they both were fighting at their hometowns and Oscar had accomplished far more than Rafael had done in his career. This was even a bigger incentive to win the match, to win his community’s respect (Kawakami 98). De La Hoya wanted to prove to this community that he was ready for greatness, it was important to win the Mexican community in southern California in order to transcend into the bigger market south of the border where the big money was.

De La Hoya could hardly be bothered by mutterings from the Ruelas camp. Ever since he won the US’s only boxing gold medal in the Barcelona Olympics, he has thought of himself as a child of destiny, born for six championships and endorsements that cross over from the Hispanic market. Even as he prepared for Ruelas, he talked casually of plans for a series of superfights- all really interested in, he says- that would carry him into the Julio Cesar Chavez country (Hoffer 1995).

Macho: Mexican vs American

While the word macho has traditionally been associated with Mexican or Latino culture, the word has recently been incorporated into American popular culture, so much that it is now widely used to describe everything from rock stars and male sex symbols in television and film to Taco Bell’s burritos.

While the word macho has traditionally been associated with Mexican or Latino culture, the word has recently been incorporated into American popular culture, so much that it is now widely used to describe everything from rock stars and male sex symbols in television and film to Taco Bell’s burritos.

When applied to entertainers, athletes, or other “superstars,” the implied meaning is clearly a positive one that connotes strength, virility, masculinity, and sex appeal. But when applies to Mexicans or Latinos, “macho” remains imbued with such negative attributes as male dominance, patriarchy, authoritarianism, and spousal abuse. Although both meanings connote strength and power, the Anglo macho is clearly a much more positive and appealing symbol of manhood and masculinity. In short, under current usage the Mexican macho oppresses and coerces women, whereas his Anglo counterpart appears to attract and seduce them,” (Mirandé 66).

The figure of Oscar De La Hoya became a commercial product of the US, comparable to the image of a Hollywood celebrity. His picture started to be placed next to images of celebrities such as Brad Pitt, Tom Cruise, and Leonardo Di Caprio as the hottest man of the 90’s in magazines like People, Cosmopolitan, Vanity, and Entertainment Weekly which specifically target female audiences. He preceded the boom of the “Latino Lover” phenomena sparkled by Ricky Martin in the late 1990’s. Once a LA DJ of POWER 106 FM described on the radio how he was giving tickets away for De La Hoya’s fight in 1997 against Hector “El Macho” Camacho, out of around 100 calls that they received, more than 70% were females who described their interest in watching the fight with comments like, “Oscar is the sexiest man alive and he is going to prove that he is the real macho when he beats Camacho” (Kawakami 126+).

The figure of Oscar De La Hoya became a commercial product of the US, comparable to the image of a Hollywood celebrity. His picture started to be placed next to images of celebrities such as Brad Pitt, Tom Cruise, and Leonardo Di Caprio as the hottest man of the 90’s in magazines like People, Cosmopolitan, Vanity, and Entertainment Weekly which specifically target female audiences. He preceded the boom of the “Latino Lover” phenomena sparkled by Ricky Martin in the late 1990’s. Once a LA DJ of POWER 106 FM described on the radio how he was giving tickets away for De La Hoya’s fight in 1997 against Hector “El Macho” Camacho, out of around 100 calls that they received, more than 70% were females who described their interest in watching the fight with comments like, “Oscar is the sexiest man alive and he is going to prove that he is the real macho when he beats Camacho” (Kawakami 126+).

Conclusion

The image of Oscar De La Hoya that was being promoted by mass media failed to represent the male immigrant community that he aspired to prove his aptitude as a boxer. Oscar could no longer be seen as a fighter from El barrio because his clean-cut public image on magazines and television did not represent the Mexican immigrant self-perception as a piscador [farmer, fruit picker] or yardero [yard cleaner]. Oscar could not achieve to be seen as part of the Mexican community in Los Angeles because he did not recognize that his celebrity lifestyle and habits represented those of a Chicano. Once Oscar was associated to be Chicano, Mexican males started to portray their insecurity and feelings of inferiority against Oscar’s image which consequently resulted in him being despised.

The image of Oscar De La Hoya that was being promoted by mass media failed to represent the male immigrant community that he aspired to prove his aptitude as a boxer. Oscar could no longer be seen as a fighter from El barrio because his clean-cut public image on magazines and television did not represent the Mexican immigrant self-perception as a piscador [farmer, fruit picker] or yardero [yard cleaner]. Oscar could not achieve to be seen as part of the Mexican community in Los Angeles because he did not recognize that his celebrity lifestyle and habits represented those of a Chicano. Once Oscar was associated to be Chicano, Mexican males started to portray their insecurity and feelings of inferiority against Oscar’s image which consequently resulted in him being despised.

Mexicans started to see that De La Hoya portrayed his Mexicanity only when convenient, specially prior to his fights, and his management was more preoccupied on gaining this community for the money they could generate as a boxing market rather than for building De La Hoya’s credibility. De La Hoya never embraced this community in obvious manners and he found rejection as reciprocal reaction.

Mexicans started to see that De La Hoya portrayed his Mexicanity only when convenient, specially prior to his fights, and his management was more preoccupied on gaining this community for the money they could generate as a boxing market rather than for building De La Hoya’s credibility. De La Hoya never embraced this community in obvious manners and he found rejection as reciprocal reaction.

Oscar De La Hoya now has lost his title, and lost his last fight that was supposed to bring him back into track to be a dangerous contestant once again. His attempt to reinforce his macho image among the immigrant community failed once again, and critics argue that it is for good. This could be one factor that has driven him to seek different outlets for his future career. Oscar released a music album last year based on the image of “the sexiest man” claimed by his female fans. He has appeared in several magazines promoting his new career as a singer. Boxing is still in consideration, but for now he has found another approach to convince his community about his Mexicanity by singing mariachi and wearing trajes de charro with a smile on his face in a Alejandro Fernandez’s style.

Bibliography

“Cold-blooded.” Sports Illustrated v. 84 (June 17 ’96) p. 70-3.

Gutmann, Matthew C. The meanings of macho: being a man in Mexico City.

Berkeley: University of California Press, c1996.

Hoffer, Richard. “Glory and sorrow.” Sports Illustrated v. 82 (May 15 ’95) p. 48-51.

“The pugilist and the professor.” Sports Illustrated v. 84 (June 10 ’96) p. 82.

Horowitz, Ruth. Honor and the American dream: culture and identity in a Chicano

community. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, c1983.

Kawakami, Tim. Golden Boy. Andrews McMeel Publishing, c2000.

Mirandé, Alfredo. Hombres y machos: masculinity and Latino culture. Boulder,

Colorado: Westview Press, c1997.

O’Brien, Rich. “El Mejor.” Sports Illustrated v. 75 (Oct. 21 ’91) p. 66-8+.

Price, S. L. “He says he’s a gladiator, but Oscar De La Hoya has yet to give a

definitive ring performance that proves he has the heart of a great

champion.” Sports Illustrated v. 92 no25 (June 19 2000) p. 80-92.

Ramos, Samuel. Profile of Man and Culture in Mexico. Translated by Peter G.

Earle. Austin: University of Texas Press, c 1962.

Sanchez, George J. Becoming Mexican American: ethnicity, culture, and identity in

Chicano Los Angeles, 1900-1945. New York: Oxford University Press, c1993.

Sammons, Jeffrey T. Beyond the ring: the role of boxing in American. Urbana:

University of Illinois Press, c1988.

Walters, John. “The throws of victory.” Sports Illustrated v. 79 (Dec. 20 ’93) p. 75

Leave a comment